Hidden Sleep Crisis: Unhoused Americans Struggle For Their Health

“I haven’t laid down in a long time,” says Greg Donald, 60, from his wheelchair inside New York’s Grand Central Station.

One of about 69,000 unhoused people in New York City, Donald says a back surgery a decade ago has left him unable to walk. And he’s often unable to sleep, staying up for 24 hours at a time.

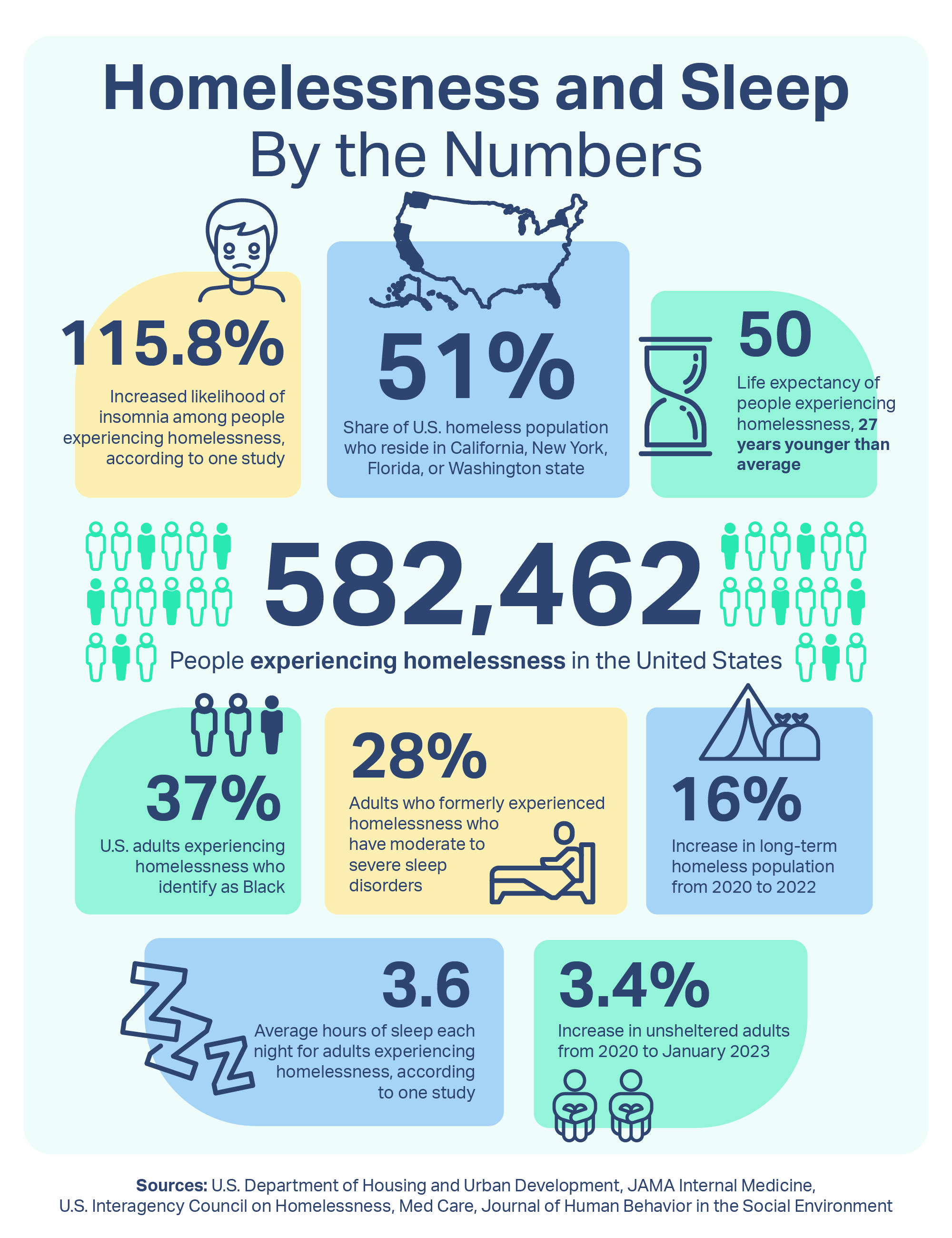

Sleep deprivation is central to the daily challenges facing Donald and the roughly 600,000 unhoused people in the United States . Although it’s tricky to define because it covers complex situations, homelessness involves unpredictable, temporary, or unsafe places to sleep, including those not created as living spaces, according to the U.S. Codes of Law .

Sleep is thus underrepresented for people experiencing homelessness, despite being one of the three pillars of health , alongside nutrition and exercise. One recent study of people experiencing homelessness in Denver found that participants slept an average of 3.6 hours in 24 hours and 2.9 hours without interruption, far fewer than the recommended seven or more hours of sleep for adults.

It’s a concerning enough issue on its own. But factor in the lack of health care that unhoused people receive, and it creates a negative cycle.

“Unhoused populations disproportionately experience health conditions,” says Christine Spadola, Ph.D., an assistant professor of social work at the University of Texas at Arlington who has studied sleep and homelessness.

According to the National Health Care for the Homeless Council, people experiencing homelessness have higher rates of illness and die on average 12 to 27 years sooner than housed adults in the U.S. Having a disability also increases the chances of experiencing homelessness.

Then there’s the issue of equity. Black adults, for example, comprise 37.3% of the U.S. homeless population3, compared to 13.6% of the overall population . Laws against resting in public, shelter policies, and employment challenges also contribute to systemic and public health inequities connected to sleep that unhoused people experience all over the U.S.

Spadola and other researchers point to the need for more integrated support and programs that are mindful of sleep education. Where to start?

Where and How Do Unhoused People Sleep?

Homelessness spans many precarious living situations. Some 60% of unhoused people sleep in sheltered, emergency, or transitional housing locations, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development3.

New York, as the nation’s largest city, has seen its shelter population quadruple in the past 40 years.

Many who stay in shelters may be families who might not have other options. Coalition for the Homeless research shows that families comprise 70% to 80% of New York Department of Homeless Services shelter residents and spend an average of 1.5 years there.

Years ago, New York’s Jawanza Williams found safety in 24-hour drop-in centers, like New York’s Ali Forney Center, which protects and advocates for LGBTQ youth.

“These drop-ins were really critical because young people need to have a place to sleep,” says Williams, now managing director of organizing for Voices of Community Activists and Leaders, which supports low-income people affected by homelessness, drugs, HIV/AIDS, and mass incarceration.

But others have different viewpoints on shelters. Donald says he prefers not to stay in them because they ask people to leave inconveniently early. That puts him among the 40% of unhoused people3 who reside in unsheltered areas deemed “not suitable for human habitation” — tents, streets, abandoned buildings, and the like.

Between 2015 and 2020, there was a 30% surge of unsheltered houseless people nationwide . Reasons for not sleeping in shelters when they’re available vary considerably, with research also documenting violence in shelters as a sleep deterrent .

Funding and shelter availability play a large role, too. And it’s not just a big-city issue. Iowa experienced a 14% loss in emergency youth shelter beds between February and October 2021 . Washington state has seen a 50% decline in government funding for shelters across the state , with $2.5 million slashed from 15 homeless services programs in rural Skagit County in 2022.

So where to sleep? In New York City, there are public-transportation venues such as the subway, though the city has vowed to crack down on riders who sleep on more than one seat or otherwise violate the Metropolitan Transit Agency’s rules of conduct. There’s outdoors, which New York is grappling with as it watches warmer-weather West Coast cities do the same.

In many situations, however, unsheltered sleep may run afoul of the law. Forty-eight states have laws restricting or prohibiting the actions of unhoused people , with a number banning some form of camping. Missouri, for instance, disallowed unauthorized sleeping on state-owned land in January 2023 , with Texas doing the same for all public land in 2021 .

Creating a Vicious Cycle

At the government level, homelessness is addressed as a public-safety issue. When you consider the sleep implications, however, it can go deeper.

“Health precedes safety, whether you’re sleeping outside or in a shelter,” Spadola says.

Researchers have been studying sleep deprivation among people experiencing houselessness. Their conclusion: Sleep problems are omnipresent but hidden in plain sight. Poor sleep makes it harder for anyone to function during the day , which impacts the ability to find employment and secure housing.

A 2021 Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness article that Spadola co-authored looked at employment among unhoused, mostly Black women in Florida. According to the article, 80% of study participants cited sleep as a barrier to finding work .

At least half of the women had a history of mental illness or substance abuse or had experienced trauma. Without prompting, participants in the study reported that where and how they sleep affected their ability to work.

“We were really surprised at how often sleep came up,” says Spadola, who conducted the research and co-wrote the article with Danielle Groton, Ph.D., assistant professor of social work at Florida Atlantic University, as part of Groton’s dissertation research.

Health care became tied up in the results, too. Groton says that women respondents said they would feel sick after not getting enough sleep the night before — or even pass out at work because of unmanaged diabetes.

“If you aren’t feeling well and are running on only two or three hours of sleep, you may also be more likely to become frustrated at work, have trouble remembering tasks, and may not present as professionally,” she says.

Having a regular bedtime routine for peaceful sleep isn’t always accessible for unhoused people, who may not have agency over their sleep schedule.

Shelter themselves also present an issue. Many shelters have curfews or only offer beds at night. That can clash with opportunities for nighttime shift work. Miss a bus after work, for example, or stay too long at an evening function, and you may be out of a bed for the night.

As much as they may cut down on the light, noise, and safety issues that someone may experience by sleeping outdoors, shelters don’t always equate to sleep hygiene.

“It is very difficult for people experiencing homelessness to do some of the things that we recommend [for sleep],” says Scott Pickett, Ph.D., associate professor of social medicine at the Florida State University College of Medicine and director of its Sleep Trauma and Emotional Processes program.

Having a regular bedtime routine for peaceful sleep isn’t always accessible for unhoused people, who may not have agency over their sleep schedule.

“Dinner is served at 8 p.m., and then it’s lights out at 10 p.m.” Spadola says.

To help promote sleep in shelters, Groton and others suggest greater scheduling flexibility and separate sleeping spaces for workers and non-workers. Some shelters have started to promote better sleep hygiene by providing sleep-friendly features, such as individual-controlled temperature and light, flexible schedules for sleeping, and locked doors for privacy and safety.

Examining the Health Implications

Even when unhoused people find safe shelter in the short or long term, they may continue to experience problems with their sleep or general health.

In 2021, a study of formerly unhoused residents in Los Angeles revealed persistent sleep problems even after they moved to permanent supportive housing. Most participants, 60% of whom were Black and who ranged from 45 to 80 years old, experienced moderate or severe sleep disturbance at a higher level (28%) than those who had never experienced homelessness (20%). Most participants also had physical or mental health conditions contributing to their sleep issues.

It’s here where the pillars of health continue to show their effect.

Got a hot tip? Pitch us your story idea, share your expertise with SleepFoundation.org, or let us know about your sleep experiences right here.

“Someone who lives unsheltered and doesn’t have access to routine check-ups might not be aware that they have developed an infection, and by the time they notice there is a concern and seek emergency medical attention [it may be too late],” Groton says. “Access to regular health care can prevent issues from developing, which is a win [for everyone] because it keeps emergency rooms and urgent cares from being crowded.”

Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (S.N.A.P.), and other programs are part of the U.S. social safety net designed to support low-income individuals and families. But navigating these safety net programs can be confusing , leaving people falling through the cracks. Donald, for instance, says he received financial assistance until it expired.

Filing paperwork in a timely way can be hard for someone experiencing houselessness, as it is for many people. Prescription management can also be a challenge, according to Groton.

“Mental health is critically important, too,” she says. “The experience of homelessness is traumatic in itself.”

References

23 Sources

-

Basic Facts About Homelessness: New York City. (December 2022) Coalition for the Homeless., Retrieved March 10, 2023.

https://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/basic-facts-about-homelessness-new-york-city/ -

Gonzalez, A., & Tyminski, Q. (2020). Sleep deprivation in an American homeless population. Sleep health, 6(4), 489–494.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32061552/ -

Annual Homelessness Assessment Report in Congress, U.S. Department of Urban Housing and Development, 2022., Accessed April 25, 2023.

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2022-AHAR-Part-1.pdf -

42 U.S. Code § 11302 – General definition of homeless individual., Retrieved March 10, 2023.

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/11302 -

Castillo M. (2015). The 3 pillars of health. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology, 36(1), 1–2.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24924551/ -

Hoops Calhoun, K., & Chassman, S. (2022). Sleep quality and quantity among adults experiencing homelessness: An ecological systems approach. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 32(6), 798-811.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10911359.2021.1968556 -

Consensus Conference Panel, Watson, N. F., Badr, M. S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D. L., Buxton, O. M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D. F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M. A., Kushida, C., Malhotra, R. K., Martin, J. L., Patel, S. R., Quan, S. F., Tasali, E., Non-Participating Observers, Twery, M., Croft, J. B., Maher, E., … Heald, J. L. (2015). Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: A Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 11(6), 591–592.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25979105/ -

National Health Care for the Homeless Council (2019, February). Homelessness and Health: What’s the Connection?, Retrieved April 10, 2023.

https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/homelessness-and-health.pdf -

Vinoski Thomas, E., & Vercruysse, C. (2019, June 14). Homelessness Among Individuals with Disabilities: Influential Factors and Scalable Solutions., Retrieved March 10, 2023.

https://www.naccho.org/blog/articles/homelessness-among-individuals-with-disabilities-influential-factors-and-scalable-solutions -

United States Census Bureau. (2022, July 1). U.S. Census Bureau quickfacts: United States. Www.census.gov; United States Census Bureau.

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045222 -

Simone, J. (2022, March). State of the Homeless 2022., Retrieved March 10, 2023.

https://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/state-of-the-homeless-2022/ -

National Alliance to End Homelessness (2021, February 26). State of Homelessness., Retrieved March 10, 2023.

https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness/ -

Agrawal, P., Neisler, J., Businelle, M. S., Kendzor, D. E., Hernandez, D. C., Odoh, C., & Reitzel, L. R. (2019). Exposure to Violence and Sleep Inadequacies among Men and Women Living in a Shelter Setting. Health behavior research, 2(4), 19.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34164609/ -

Crawford, K. (2022, January 10). Foster care organizations struggle to find homes, youth shelters amid COVID-19. Iowa Public Radio.

https://www.iowapublicradio.org/ipr-news/2022-01-10/foster-care-organizations-struggle-to-find-homes-youth-shelters-amid-covid-19 -

Greenstone, S. (2023, March 6). Skagit and other counties may close homeless shelters due to drop in mortgage fees. KNKX Public Radio.

https://www.knkx.org/government/2023-03-05/washington-counties-close-homeless-shelters-mortgage-fees -

The Subway Safety Plan The Subway Safety Plan. (n.d.)., Retrieved June 6, 2023, from

https://www.nyc.gov/assets/home/downloads/pdf/press-releases/2022/the-subway-safety-plan.pdf -

Housing Not Handcuffs (November 2021). National Homelessness Law Center., Retrieved March 10, 2023.

https://homelesslaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-HNH-State-Crim-Supplement.pdf -

Mary Grace, P. (n.d.). SB1106 – Modifies provisions relating to funding for housing programs. Www.senate.mo.gov., Retrieved June 6, 2023, from

https://www.senate.mo.gov/22info/BTS_Web/Bill.aspx?SessionType=R&BillID=74320719 -

Texas Legislature Online. (n.d.). Texas Legislature Online – 87(R) History for HB 1925. Capitol.texas.gov., Retrieved June 6, 2023, from

https://capitol.texas.gov/BillLookup/History.aspx?LegSess=87R&Bill=HB1925 -

Wilckens, K. A., Woo, S. G., Kirk, A. R., Erickson, K. I., & Wheeler, M. E. (2014). Role of sleep continuity and total sleep time in executive function across the adult lifespan. Psychology and aging, 29(3), 658–665.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25244484/ -

Groton, D. B., & Spadola, C. (2021). “I ain’t getting enough rest”: A Qualitative Exploration of Sleep among Women Experiencing Homelessness. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10530789.2021.1961991 -

Henwood, B. F., Rhoades, H., Dzubur, E., Madden, D. R., Redline, B., & Brown, R. T. (2021). Investigating Sleep Disturbance and Its Correlates Among Formerly Homeless Adults in Permanent Supportive Housing. Medical care, 59(Suppl 2), S206–S211.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7959063/ -

De Gregorio, S., Brooks Smith, R., Painter, G., & Creighton, M. (2021, August). Examining the Complex Social Safety Net for Low-Income Working Families: How Benefits and Resources Respond to Increases in Wages.

https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Social-Safety-Net_Full-Report_FINAL_10.22.21.pdf