Non-24 Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder Symptoms & Diagnosis

Most people with Non-24 Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder (N24SWD) notice sporadic symptoms at first, such as occasional bouts of nighttime insomnia or excessive daytime sleepiness. Because N24SWD is characterized by a gradual delay in the sleep-wake cycle (with rarer instances characterized by a gradual advance), individuals with this disorder sometimes experience few to no symptoms at all. Other times, symptoms may be severe.

To make matters worse, efforts to fight this delay by adhering to a consistent sleep schedule can result in severe sleep deprivation. Ultimately, the cycle comes full circle, and individuals experience temporary relief of symptoms as their sleep habits realign with their schedules.

What Are the Most Common Symptoms of Non-24 Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder?

The most common symptoms of N24SWD are nighttime insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness , also called hypersomnolence. Since these symptoms come and go depending on the alignment of sleep habits with external schedules, N24SWD may go unnoticed for some time. N24SWD can also co-occur) with other sleep disorders, like obstructive sleep apnea and delayed sleep-wake phase disorder (DSWPD). In fact, a history of DSWPD may precede the onset of N24SWD, and it is common for those with sleep-wake rhythm disorders to be more active at night preceding symptom onset .

As N24SWD progresses, individuals may experience additional symptoms of sleep deprivation, including fatigue, depression, and attention and memory problems. Abnormal melatonin levels and general weakness are also observed.

Psychiatric symptoms are especially prevalent, caused both by sleep loss and the significant impact of the disorder on social schedules. One study monitoring sighted N24SWD patients found that 34% of participants developed major depression after the onset of sleep symptoms and that their depressive symptoms worsened when sleep habits misaligned with a regular day/night schedule. This study also noted that the cause of depression symptoms is likely twofold, with both sleep loss and the isolating nature of the disorder to blame.

What Are the Risk Factors for Developing Non-24 Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder?

N24SWD most often occurs in blind populations, and it is known to affect 55-70% of totally blind people . N24SWD is one of a group of disorders impacting circadian rhythm, which is the approximately 24-hour internal clock that syncs our sleep-wake cycle to the natural cycle of day and night. The circadian rhythm of people is naturally a bit longer than 24 hours. So, without the ability to recognize stabilizing external cues, or “zeitgebers,” like light, blind individuals are especially vulnerable to misalignments in circadian rhythm that lead to circadian rhythm sleep disorders , such as N24SWD.

Although N24SWD is far more typical in blind individuals, there is an unclear number of sighted patients who develop N24SWD from other causes. Sighted people more at risk for N24SWD include males, those in their teens and twenties, those who work odd schedules, and those who live or work in low-light environments. Other more unique causes of N24SWD have been observed, including unsuccessful attempts to treat delayed sleep disorders , and brain trauma.

How Is Non-24 Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder Diagnosed?

Since the symptoms of N24SWD come and go, the disorder can be difficult to diagnose without several weeks of documenting sleep. According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD), the diagnosis of N24SWD requires difficulty falling asleep or waking up, a progressive delay in the sleep phase, and an inability to entrain (adjust to) a regular 24-hour day for six weeks or longer.

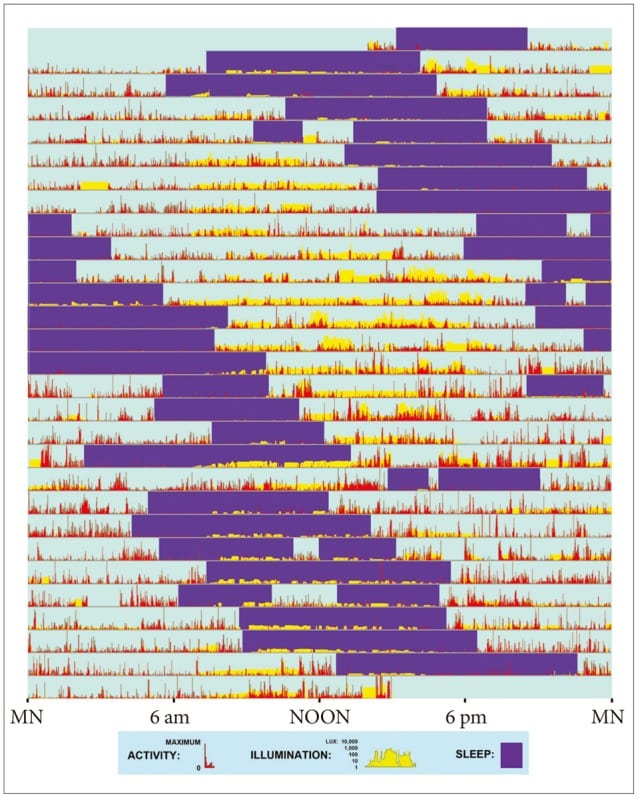

An efficient method of measuring sleep habits over time is actigraphy . Actigraphic devices are wristwatch-like monitors that can track periods of sleep and wakefulness over time and provide a visualization of the progressive delay in the sleep-wake cycle that indicates N24SWD. The image below illustrates a case study of an N24SWD patient’s sleep habits over a several-week period, with red bars representing waking periods and purple bars representing sleep.

To help with diagnoses, doctors might also ask patients to keep their own sleep logs or sleep diaries. Doctors might also order polysomnography or overnight sleep study. While polysomnography cannot measure the change in sleeping habits over time, it can be used to rule out other sleep disorders . Additionally, questionnaires like the MEQ (Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire) may be used, but there is insufficient evidence to support the usefulness of self-reported questionnaires.

How Is Non-24 Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder Different From Other Disorders?

Since the symptoms of N24SWD overlap with other circadian rhythm disorders , it is sometimes overlooked or misdiagnosed. The delay in sleep onset may make N24SWD appear to be delayed sleep-wake phase disorder (DSWPD), a disorder that causes a tendency to stay up late into the night and have difficulty waking in the morning.

The variation in sleep times associated with N24SWD may also be confused with irregular sleep-wake rhythm disorder (idiopathic hypersomnia). In this disorder, people wake and sleep with no apparent pattern, which makes it difficult for them to adhere to consistent schedules and obligations.

Although these disorders are similar, N24SWD is different from both in that it features a delay in the sleep-wake cycle that progresses consistently over time until it cycles all the way around the clock.

How Can I Talk to My Doctor About Non-24 Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder?

If you are suffering from chronic fatigue, excessive daytime sleepiness, or insomnia, you might want to talk to your doctor about your symptoms. Keeping a sleep log can assist your doctor in finding the appropriate diagnosis. A sleep log helps document changes in your sleep-cycle over a period of time, revealing whether or not there is a progressive pattern that may indicate N24SWD. When you see a doctor, they may ask you questions about when you fall asleep and wake up, how long it takes you to fall asleep, how energized you feel during the day, and what eating and exercise routines you practice.

Keep in mind that fighting against N24SWD on your own or leaving it untreated can lead to chronic sleep deprivation and severely impact work, social activities, and relationships. Depending on how it affects a person, N24SWD can be considered a disability. When it is disabling, employers and schools are required to make reasonable accommodations, including modified schedules.

Still have questions? Ask our community!

Join our Sleep Care Community — a trusted hub of sleep health professionals, product specialists, and people just like you. Whether you need expert sleep advice for your insomnia or you’re searching for the perfect mattress, we’ve got you covered. Get personalized guidance from the experts who know sleep best.

References

11 Sources

-

Malkani, R. G., Abbott, S. M., Reid, K. J., & Zee, P. C. (2018). Diagnostic and treatment challenges of sighted non-24-hour sleep-wake disorder. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. , 14(4), 603–613.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29609703/ -

Yamadera, H., Takahashi, K., & Okawa, M. (1996). A multicenter study of sleep-wake rhythm disorders: Clinical features of sleep-wake rhythm disorders. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 50(4), 195–201.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9201776/ -

Hayakawa, T., Uchiyama, M., Kamei, Y., Shibui, K., Tagaya, H., Asada, T., Okawa, M., Urata, J., & Takahashi, K. (2005). Clinical analyses of sighted patients with non-24-hour sleep-wake syndrome: a study of 57 consecutively diagnosed cases. Sleep, 28(8), 945–952.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16218077/ -

Emens, J. S., & Eastman, C. I. (2017). Diagnosis and treatment of non-24-h sleep-wake disorder in the blind. Drugs, 77(6), 637–650.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28229310/ -

Garbazza, C., Bromundt, V., Eckert, A., Brunner, D. P., Meier, F., Hackethal, S., & Cajochen, C. (2016). Non-24-hour sleep-wake disorder revisited – A case study. Frontiers in Neurology, 7, 17.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26973592/ -

Sack, R. L., Auckley, D., Auger, R. R., Carskadon, M. A., Wright, K. P., Vitiello, M. V., & Zhdanova, I. V. (2007). Circadian rhythm sleep disorders: Part II, advanced sleep phase disorder, delayed sleep phase disorder, free-running disorder, and irregular sleep-wake rhythm. Sleep, 30(11), 1484–1501.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18041481/ -

Oren, D. A., & Wehr, T. A. (1992). Hypernyctohemeral syndrome after chronotherapy for delayed sleep phase syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine, 327(24), 1762.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1435929/ -

Uchiyama, M., Shibui, K., Hayakawa, T., Kamei, Y., Ebisawa, T., Tagaya, H., Okawa, M., & Takahashi, K. (2002). Larger phase angle between sleep propensity and melatonin rhythms in sighted humans with non-24-hour sleep-wake syndrome. Sleep, 25(1), 83–88.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11833864/ -

Kripke, D. F., Klimecki, W. T., Nievergelt, C. M., Rex, K. M., Murray, S. S., Shekhtman, T., Tranah, G. J., Loving, R. T., Lee, H. J., Rhee, M. K., Shadan, F. F., Poceta, J. S., Jamil, S. M., Kline, L. E., & Kelsoe, J. R. (2014). Circadian polymorphisms in night owls, in bipolars, and in non-24-hour sleep cycles. Psychiatry Investigation, 11(4), 345–362.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25395965/ -

Morgenthaler, T. I., Lee-Chiong, T., Alessi, C., Friedman, L., Aurora, R. N., Boehlecke, B., Brown, T., Chesson, A. L., Jr, Kapur, V., Maganti, R., Owens, J., Pancer, J., Swick, T. J., Zak, R., & Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2007). Practice parameters for the clinical evaluation and treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep, 30(11), 1445–1459.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18041479/ -

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). (n.d.). Circadian Rhythm Disorders., Retrieved February 13, 2021, from

https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/circadian-rhythm-disorders