Chronotypes: Definition, Types, & Effect on Sleep

- Chronotypes are natural preferences of the body for wakefulness and sleep.

- An individual’s chronotype is influenced by genetics and driven by their circadian rhythm.

- Chronotypes affect sleep as well as performance and activity throughout the day.

- Adapting to one’s natural chronotype can improve your sleep quality, energy, and mood.

Chronotype is the natural inclination of your body to sleep at a certain time, or what most people understand as being an early bird versus a night owl. In addition to regulating sleep and wake times, chronotype has an influence on appetite, exercise, and core body temperature. It is responsible for the fact that you feel more alert at certain periods of the day and sleepier at others.

What Determines Chronotype?

Emerging evidence shows that chronotype likely has a strong genetic component . Among other things, having a longer allele on the PER3 circadian clock gene has been tied to morningness. Some researchers postulate that the variation in chronotype might have been a survival technique that evolved in hunter-gatherers . The theory is that by taking turns sleeping, there would always be someone awake to keep watch.

Is Your Troubled Sleep a Health Risk?

A variety of issues can cause problems sleeping. Answer three questions to understand if it’s a concern you should worry about.

For research purposes, scientists have developed several questionnaires that categorize subjects by morningness versus eveningness tendencies. In truth, chronotypes fall on a spectrum , with most people lying somewhere in between.

Two of the most popular questionnaires are the Morning-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) and the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire (MCTQ). Each of these approaches determine chronotype from a slightly different angle, with the MCTQ focusing on actual wake and sleep times and the MEQ asking questions that encompass a range of activities such as meal and exercise times.

One of the most popular online quizzes was made by Dr. Michael Breus, who describes four kinds of chronotypes, based on sleep-wake patterns seen in animals. Answering his online chronotype quiz will tell you whether you are more of a bear, wolf, lion, or dolphin .

What Is My Chronotype?

Chronotype can vary from person to person depending on genetics, age, and other factors. Some scientists believe that chronotype may differ according to geographical location as well, due to changes in daylight hours. To figure out your chronotype, think about your sleeping preferences, energy levels throughout the day, meal timing, and other facets of your circadian rhythm.

While these types can give you a general idea of your ideal schedule, there will always be variations from person to person. Whether you identify with an animal chronotype or whether you simply know deep in your heart that you prefer being awake at night, having a better understanding of how you are wired may help improve your sleep quality and quality of life.

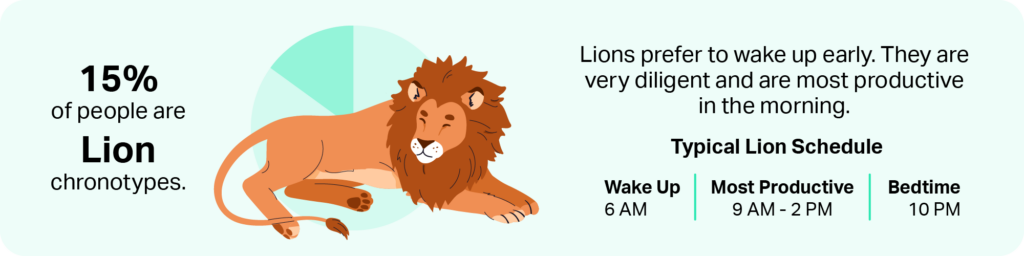

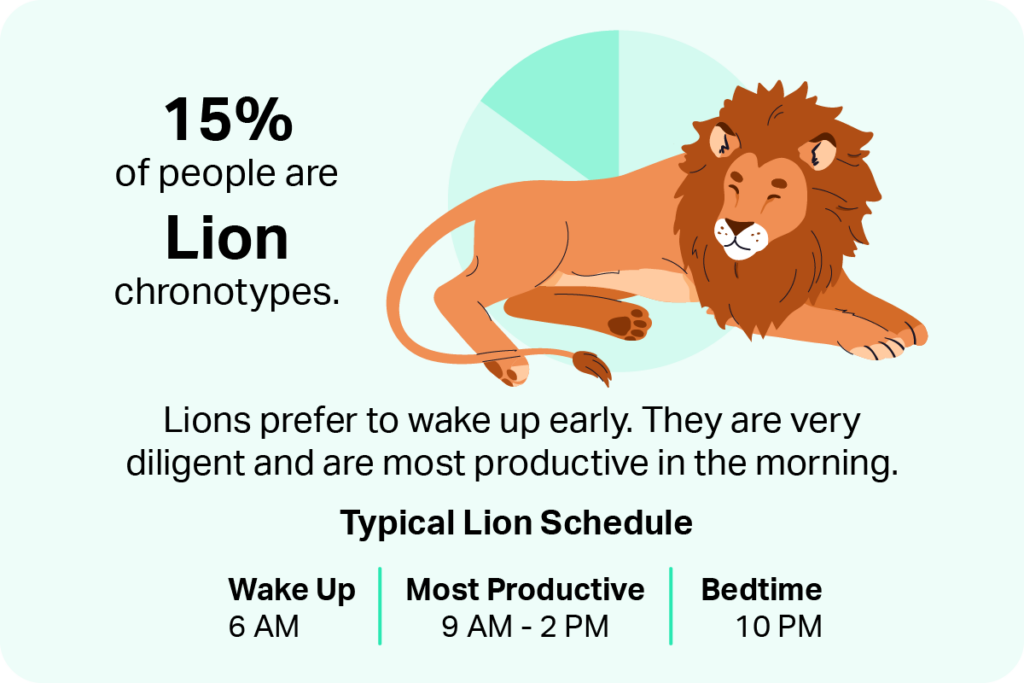

Lion

The lion chronotype stands in for the early bird. These individuals wake up early and are most productive in the morning, but may have more trouble following a social schedule in the evenings. Personality traits associated with morningness include conscientiousness and agreeableness.

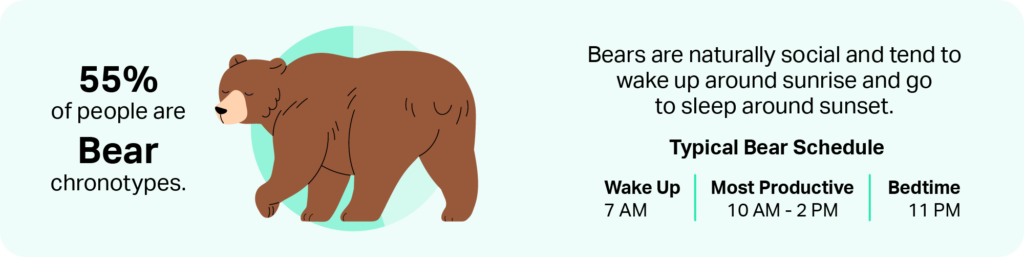

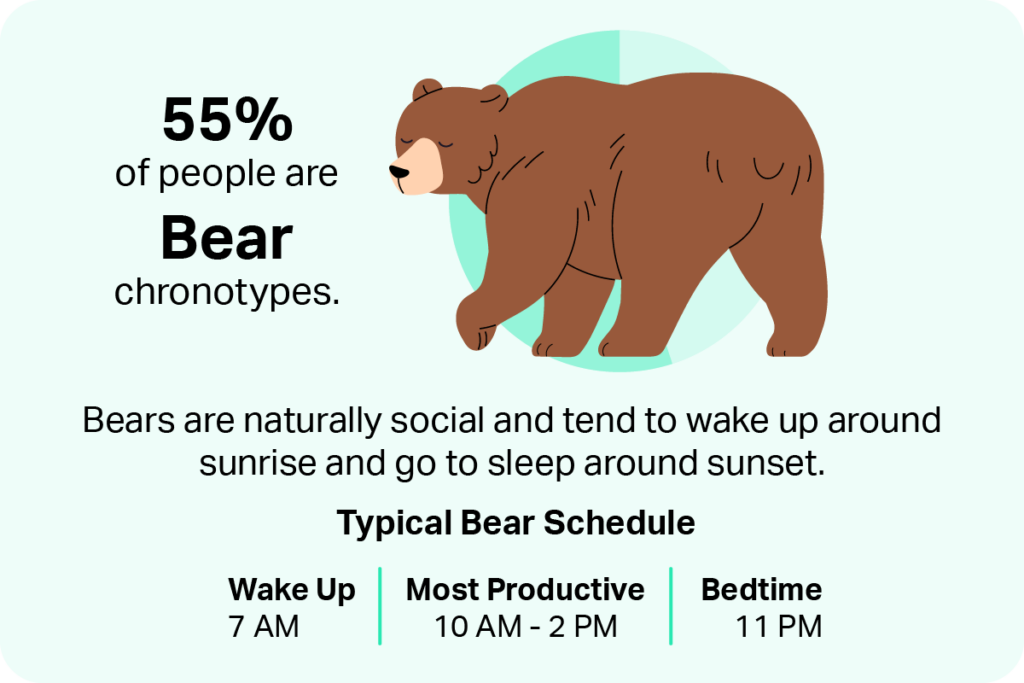

Bear

According to Dr. Breus, the bear chronotype makes up about 55% of the population. People with this intermediate chronotype tend to follow the sun. They do well with traditional office hours but also have no problem maintaining a social life in the evenings.

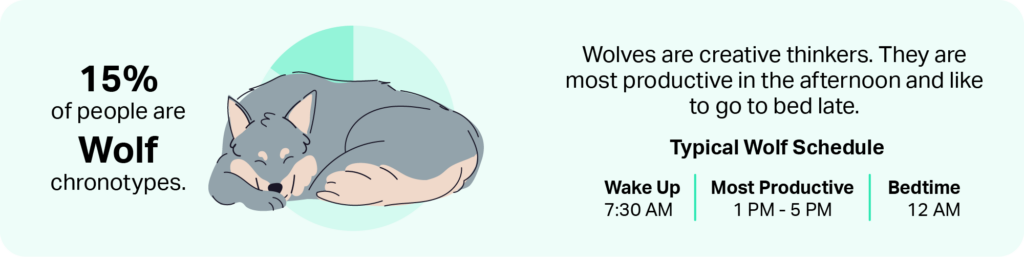

Wolf

The wolf chronotype is equivalent to the classic night owl, and is believed to make up approximately 15% of the population. Traits typically related to eveningness include neuroticism and openness.

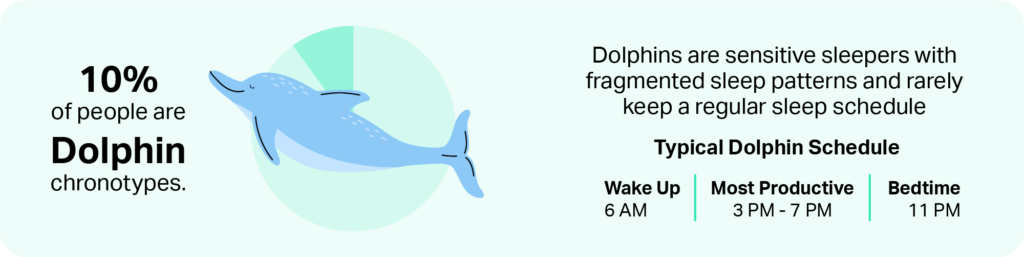

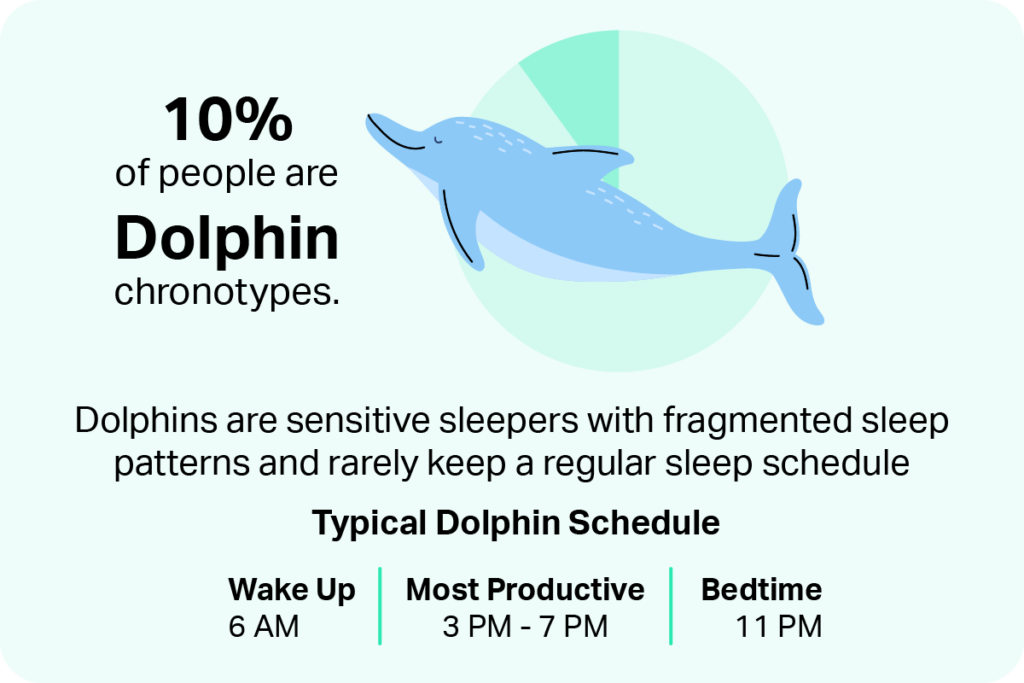

Dolphin

The dolphin chronotype is based on the ability of real dolphins to stay alert even while sleeping. Human “dolphins” are best described as insomniacs.

Chronotype vs. Circadian Rhythm

Sleep chronotype is closely related to circadian rhythm, which controls the day-to-day sleep-wake cycle. Chronotype does not influence total sleep time. However, while circadian rhythm can be “trained” by adhering to a strict schedule, the underlying chronotype exists on a more permanent basis.

If most adults need at least seven hours of sleep a night, this is usually much easier to accomplish for someone with a preference to turn in early. Thus, a person naturally inclined to stay up late may be able to wake up at 7 am for work, but they may not be productive until later in the day. For this reason, “night owls” have historically faced more difficulty adapting to typical work schedules.

Scientists consider it very difficult to purposely change your chronotype, though it may shift throughout the course of your life. As a general rule, most children have an early chronotype. In adolescence, chronotype is pushed back, leading to the myth that teenagers are lazy because they find it difficult to wake up for school. Chronotype then gradually shifts earlier and earlier upon entering adulthood.

When a person’s natural chronotype comes into conflict with the demands of their schedule, this is termed social jetlag . People who have a later chronotype may suffer from social jetlag and feel permanently tired if they need to wake up early for work or school. Likewise, those who prefer to go to bed earlier may not do well with social or cultural activities that are programmed later in the evening. For both groups, trying to perform activities that require concentration or creativity may be difficult at non-peak times.

Why Is Chronotype Important?

Multiple studies have found associations between chronotype and personality. Morning people tend to perform better in school , while evening types may have more of an aptitude for creative thinking. It is difficult to say whether these traits are innate or whether they are due to secondary factors, such as the fact that school tends to start early in the day and many creative professions require people to be active in the evening.

Evening people tend to have more flexible sleep schedules, be less physically active, and sleep less on weekdays, increasing their risk for sleep apnea, obesity, type 2 diabetes, mental disorders, and metabolic syndrome. Eveningness is also linked to impulsivity, anger, depression, and anxiety, as well as a host of negative habits including risk-taking , skipping breakfast and eating more in the evening , and using more electronic media .

It’s important to remember that chronotype likely interacts with many other factors to produce these trends. For example, a propensity for substance abuse in evening types may arise as a side-effect of depression and anxiety, which were in turn provoked by sleep deprivation due to social jetlag. Therefore, while some personality traits may depend on genetics, they are more likely the result of irregular sleep schedules and a mismatch between chronotype and work schedule.

For those who must adhere to a routine that does not match their chronotype, melatonin supplements, light therapy, or careful attention to sleep hygiene habits may help shift circadian rhythm to reduce insomnia and the effects of social jetlag. However, most people find they are unable to permanently change their chronotype.

Still have questions? Ask our community!

Join our Sleep Care Community — a trusted hub of product specialists, sleep health professionals, and people just like you. Whether you’re searching for the perfect mattress or need expert sleep advice, we’ve got you covered. Get personalized guidance from the experts who know sleep best.

References

16 Sources

-

Kalmbach, D. A., Schneider, L. D., Cheung, J., Bertrand, S. J., Kariharan, T., Pack, A. I., & Gehrman, P. R. (2017). Genetic basis of chronotype in humans: Insights from three landmark GWAS. Sleep, 40(2), zsw048.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28364486/ -

Archer, S. N., Robilliard, D. L., Skene, D. J., Smits, M., Williams, A., Arendt, J., & von Schantz, M. (2003). A length polymorphism in the circadian clock gene Per3 is linked to delayed sleep phase syndrome and extreme diurnal preference. Sleep, 26(4), 413–415.

https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/sleep/26.4.413 -

Samson, D. R., Crittenden, A. N., Mabulla, I. A., Mabulla, A., & Nunn, C. L. (2017). Chronotype variation drives night-time sentinel-like behaviour in hunter-gatherers. Proceedings. Biological sciences, 284(1858), 20170967.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28701566/ -

Roenneberg, T., Kuehnle, T., Juda, M., Kantermann, T., Allebrandt, K., Gordijn, M., & Merrow, M. (2007). Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep medicine reviews, 11(6), 429–438.

https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1087079207000895 -

Roenneberg T. (2015). Having Trouble Typing? What on Earth Is Chronotype?. Journal of biological rhythms, 30(6), 487–491.

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0748730415603835 -

Breus, M. (2018, November). Learn the perfect hormonal time to sleep, eat and have sex | Michael Breus | TEDxManhattanBeach. TED Talks.

https://www.ted.com/talks/michael_breus_learn_the_perfect_hormonal_time_to_sleep_eat_and_have_sex/transcript -

Randler, C., Schredl, M., & Göritz, A. S. (2017). Chronotype, sleep behavior, and the big five personality factors. Sage Open, 7(3).

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2158244017728321 -

Fischer, D., Lombardi, D. A., Marucci-Wellman, H., & Roenneberg, T. (2017). Chronotypes in the US – Influence of age and sex. PloS one, 12(6), e0178782.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28636610/ -

Rutters, Femke et al. “Is social jetlag associated with an adverse endocrine, behavioral, and cardiovascular risk profile?.” Journal of biological rhythms vol. 29,5 (2014): 377-83.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25252710/ -

Enright, T., & Refinetti, R. (2017). Chronotype, class times, and academic achievement of university students. Chronobiology international, 34(4), 445–450.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07420528.2017.1281287 -

Gjermunds, N., Brechan, I., Johnsen, S., & Watten, R. G. (2019). Musicians: Larks, Owls or Hummingbirds?. Journal of circadian rhythms, 17, 4.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31118949/ -

Hittle, B. M., & Gillespie, G. L. (2018). Identifying shift worker chronotype: implications for health. Industrial health, 56(6), 512–523.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29973467/ -

Gowen, R., Filipowicz, A., & Ingram, K. K. (2019). Chronotype mediates gender differences in risk propensity and risk-taking. PloS one, 14(5), e0216619.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31120931/ -

Roßbach, S., Diederichs, T., Nöthlings, U., Buyken, A. E., & Alexy, U. (2018). Relevance of chronotype for eating patterns in adolescents. Chronobiology international, 35(3), 336–347.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07420528.2017.1406493 -

Cespedes Feliciano, E. M., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Quante, M., Redline, S., Oken, E., & Taveras, E. M. (2019). Chronotype, Social Jet Lag, and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Early Adolescence. JAMA pediatrics, 173(11), 1049–1057. Advance online publication.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31524936/ -

Cox, R. C., & Olatunji, B. O. (2019). Differential associations between chronotype, anxiety, and negative affect: A structural equation modeling approach. Journal of affective disorders, 257, 321–330.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31302521/