What Do We Really Think About Adults Who Sleep In?

- According to a survey of workers, 60.9% have respect for co-workers who start their day later, compared to 67.9% who respect those starting earlier.

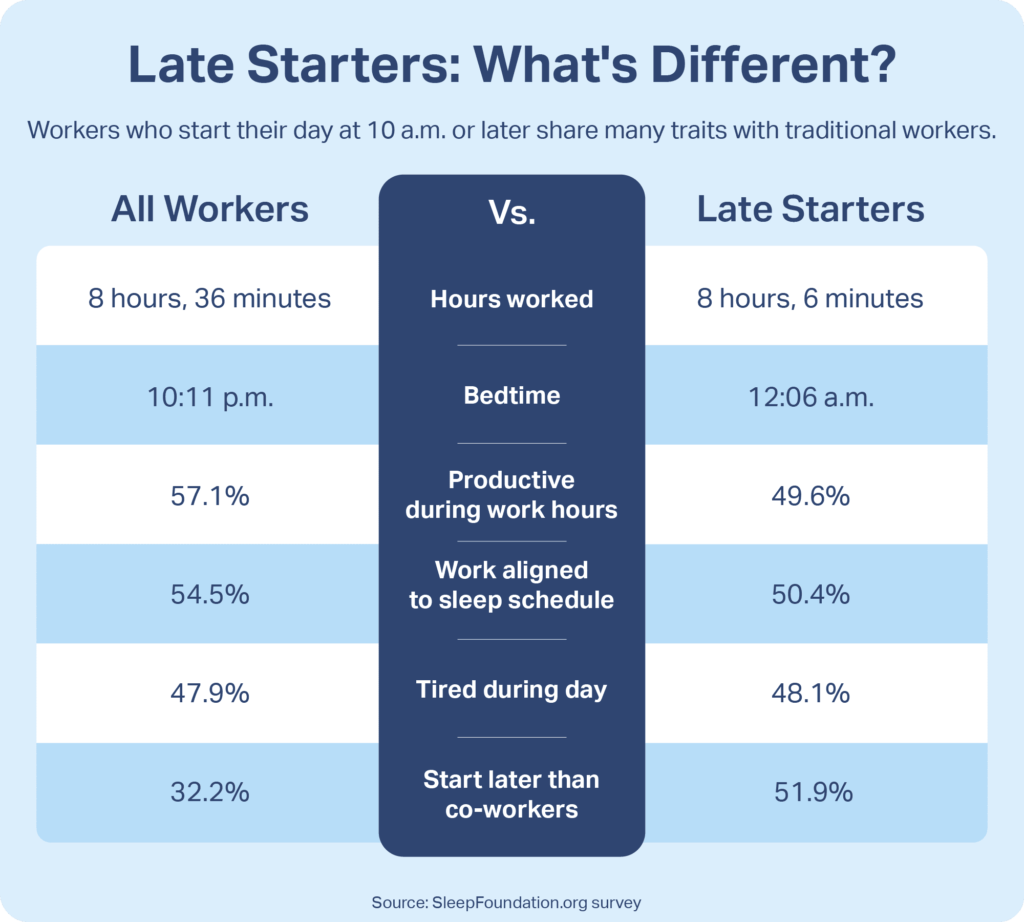

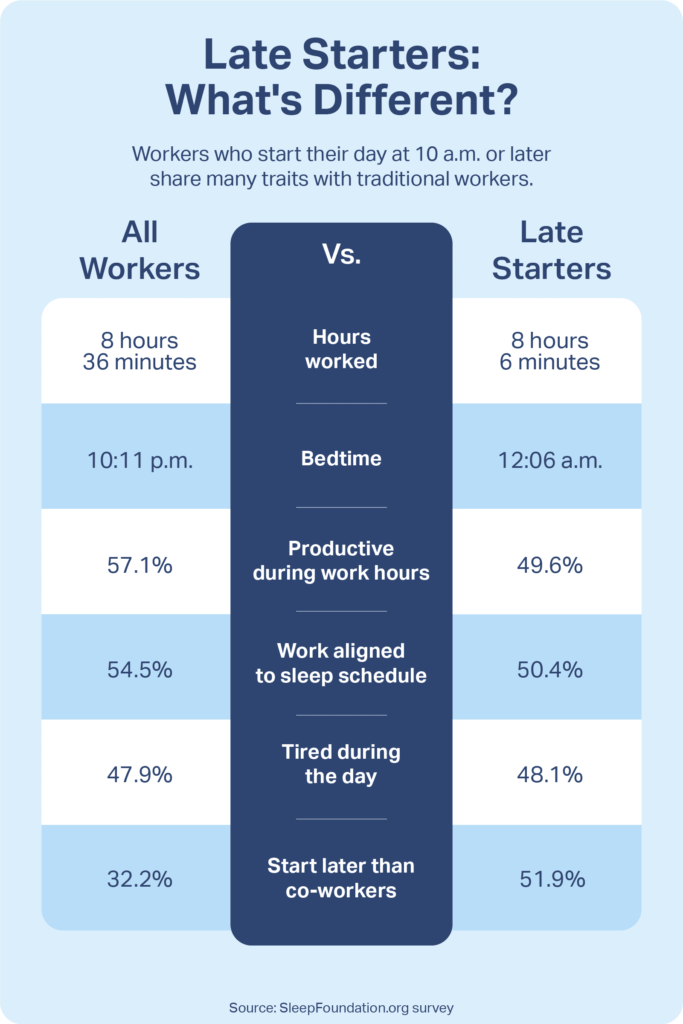

- 57.1% of workers feel most productive between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m.

- 54.5% of workers say their work schedule is generally aligned to their sleep schedule.

- 19.3% of workers who start their workday at 10 a.m. or later feel shunned because of their working hours, below the average of 26.4% for all workers.

- 52.6% of managers or people with direct reports say they nap during the workday.

People want more work flexibility, with 95% of respondents to the August 2022 Future Forum Pulse survey calling for more scheduling freedom. The pandemic has forced more employers to answer this call, leaving workers who prefer to sleep in to have their chance to do so.

No more clocking in at 8 a.m.? Great! But do managers and co-workers give these late risers the same respect as others?

Not so fast.

Researchers have uncovered a bias among managers against late-starters. But some of the same researchers found that aligning your work clock to your natural sleep clock, also known as your circadian rhythms, can optimize productivity .

So can we actually have it both ways, with the not-so-early bird getting the actual worm, solid sleep, and the respect of co-workers?

SleepFoundation.org asked more than 1,250 professionals working in the U.S. what they really think when co-workers stroll into the office right before lunch and how they feel about their own work-sleep balance.

As it turns out, we are pretty cool with our own schedules, regardless of what they are. And we might be a little judgy.

Do We Respect People With Later Work Schedules?

To understand how we work and sleep, let’s start with the basics. More than half (57.1%) of respondents say they feel most productive during the traditional workday, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Most respondents (54.5%) say their workday is generally aligned to their ideal sleep schedule, and 51.6% say they get enough sleep during the week. And yes, about the same amount (56.6%) start their workday at 8 a.m. or earlier.

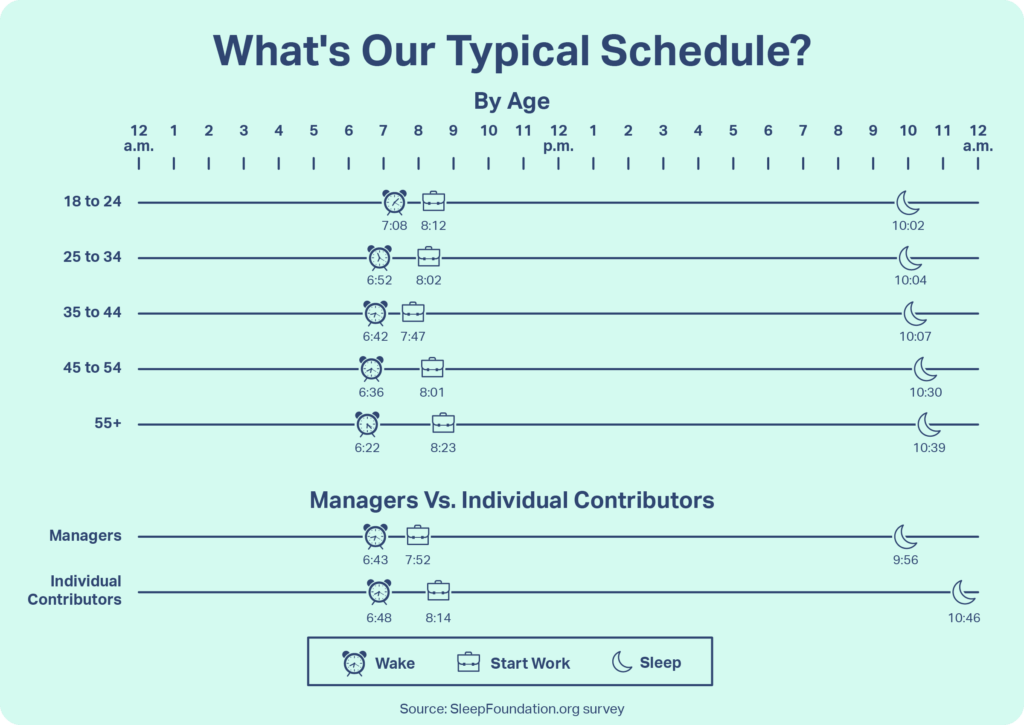

The average adult in the survey wakes up at 6:45 a.m., starts work at 8:01 a.m., and goes to bed at 10:11 p.m.

Then there’s everyone else.

While 67.9% of survey respondents say they respect co-workers who start earlier than they do, that drops to 60.9% when asked about respecting coworkers who start later.

Generationally, the divide is largest among respondents ages 18 to 24, with 67.5% respecting co-workers who start earlier and 56.1% respecting those who start later. Managers are more likely to respect late-starters (63.5%) than individual contributors are (54.9%).

All professionals surveyed had some control over the hours they work — i.e., they didn’t work shifts or on an ever-changing, as-needed basis — and worked with others with similar control. They averaged 8 hours, 36 minutes of work each day.

On the low end: workers who started their jobs at 10 a.m. or later, who comprised 10.8% of respondents and worked about a half-hour less at 8 hours, 6 minutes.

But half (50.4%) of those late-starters disagreed that they’d be better at their jobs if they worked traditional hours. They just fit the hours in differently.

Why People Work the Hours They Do

Those “traditional” hours are perhaps literally a tradition more than anything else. Before electricity, daylight hours set the workday. Farm workers rose early with the sun and went to bed early.

It’s an outdated mindset, says Melissa E. Milanak, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, South Carolina, and founder of MIND Impact Consulting. Think of it as: “I had to get up and work so you need to get up and work,” she says.

Average work-start times varied among age groups in the survey, with 35-to-44-year-olds starting the earliest, at 7:47 a.m. Workers ages 55 and older started the latest, at 8:23 a.m.

The older respondents were, the more likely they were to wake up early and go to bed late, as well. This may be because of the sleep issues we may incur as we age.

Across all professions, 50% to 55% of respondents say their work hours were aligned to their sleeping schedule. Those in education were a bit lower, at 49.5%, with 52.4% saying they’d prefer to start their workday later.

Although we typically think of tech workers as those who do start later, thanks to remote work, late start times were spread across industries in the SleepFoundation.org survey. Fields such as healthcare, arts and entertainment, retail, and hotel and food services were well-represented among workers who started their day at 10 a.m. or later.

Chronotypes, Not Our Bosses, Set Our Sleep Schedules

So why do we sleep when we do? It has to do with our chronotype, which is our body’s inclination of when we feel sleepy or alert. Several factors , including genetics , influence where on the spectrum our chronotype falls.

Understanding your chronotype, whether you’re an early bird or a night owl, can help you set your ideal work schedule, if your job allows it.

Can you retrain your chronotype, as survey results hint at? While that’s possible for your circadian rhythms, it’s not for your chronotype.

“There are some things you can do to fool your biological systems into thinking that you’re in a different time zone than you actually are, but those are not actually changing the chronotype itself,” says Christopher M. Barnes, Ph.D., a professor of management in the Michael G. Foster School of Business at the University of Washington who leads research on how sleep impacts our work. “Chronotypes do change over longer periods of time, like over the course of a lifetime.”

Barnes co-authored both aforementioned research papers about aligning work schedules to sleep schedules and the possible bias against late-starters. He says leaders still devalue sleep , as though it’s a badge of honor.

“[They’ll say] sleep is not a good use of their time [or] they’re too important to sleep,” he says.

Studies show the effects of poor sleep on job performance. Barnes agrees that not getting enough sleep makes us more vulnerable to making poor decisions on the job.

“It undermines our ability to exert self-control,” he says.

How We Cope When Our Sleep and Work Are Misaligned

The problem-solving abilities we use in our daily work may come in handy in other ways.

Dannie Lynn Fountain, a 28-year-old human-resources professional in Seattle and self-described night owl, started composing emails at night and scheduling them to arrive in the morning. This gave the impression she was an early riser — and flexible. That flexibility can be good for managers, too, she says.

“If you are operating from a place of flexibility, to begin with, it might be seen as a benefit to your company,” Fountain says.

Naps are another way workers have coped. Among survey respondents, 42.7% of workers nap or sleep during a break on a typical work day. More than half of managers do it (52.6%) but just 21.8% of individual contributors.

And if there is a bias against workers who start later, we might not always be feeling it. Of the survey respondents who start their workdays at 10 a.m. or later, only 19.3% feel shunned because of their working hours — below the average of 26.4% for all workers. Even fewer (14.8%) say they’ve been passed over for a promotion because of those hours.

Workplace education about sleep also can come into play. About half of respondents (49.6%) say their company’s wellness program has a sleep component.

“People are now recognizing that getting quality sleep is actually a priority for them and businesses,” Milanak says.

“When we are supporting better sleep for our employees, that is going to have some of the best impacts on productivity.”

Methodology

The survey commissioned by SleepFoundation.org was conducted on the online survey platform Pollfish between Sept. 20 and 21, 2022. Results are from 1,250 survey participants who were ages 18 and older and lived in the United States at the time of the survey. All attested to working in a professional setting with others with flexible work schedules and to answering the survey questions truthfully and accurately.

References

7 Sources

-

Future Forum Pulse (2022, July)

https://slack.com/blog/news/leveling-the-playing-field-in-the-new-hybrid-workplace -

Yam, K. C., Fehr, R., & Barnes, C. M. (2014). Morning employees are perceived as better employees: employees’ start times influence supervisor performance ratings. The Journal of applied psychology, 99(6), 1288–1299., Retrieved Oct. 21, 2022, from

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24911178/ -

Barnes, C. M., Guarana, C. L., Nauman, S., & Kong, D. T. (2016). Too tired to inspire or be inspired: Sleep deprivation and charismatic leadership. The Journal of applied psychology, 101(8), 1191–1199., Retrieved Oct. 21, 2022, from

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27159583/ -

Owens, J. A. (2022, June 6). Pharmacotherapy for insomnia in children and adolescents: A rational approach. In R. D. Chervin (Ed.). UpToDate., Retrieved Oct. 18, 2022, from

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-insomnia-in-children-and-adolescents-a-rational-approach -

Kalmbach, D. A., Schneider, L. D., Cheung, J., Bertrand, S. J., Kariharan, T., Pack, A. I., & Gehrman, P. R. (2017). Genetic Basis of Chronotype in Humans: Insights From Three Landmark GWAS. Sleep, 40(2), zsw048., Retrieved Oct. 21, 2022, from

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28364486/ -

Barnes, C. M., Awtrey, E., Lucianetti, L., & Spreitzer, G. (2020). Leader sleep devaluation, employee sleep, and unethical behavior. Sleep health, 6(3), 411–417.e5., Retrieved Oct. 21, 2022, from

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32331865/ -

Rosekind, M. R., Gregory, K. B., Mallis, M. M., Brandt, S. L., Seal, B., & Lerner, D. (2010). The cost of poor sleep: workplace productivity loss and associated costs. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 52(1), 91–98., Retrieved Oct. 21, 2022, from

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20042880/