Can’t Eat, Can’t Sleep: Rest Doesn’t Come Easy in a Food Desert

When Darthula Young needed groceries, she drove from her Chicago home to the suburb of Oak Park, Illinois.

“That was probably where the closest stores were, where you could get quality food, quality meat,” says Young, 73, who lived in Chicago’s West Garfield Park neighborhood for more than 40 years before a recent move to the city’s south suburbs.

End to end, it’s about a 15-minute drive, twice as much by foot and public transportation.

Oak Park is home to numerous historic houses designed by famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright, as well as the birthplace of Ernest Hemingway.

West Garfield Park is home to the most violent ZIP code, 60624, in a city with a reputation for violence.

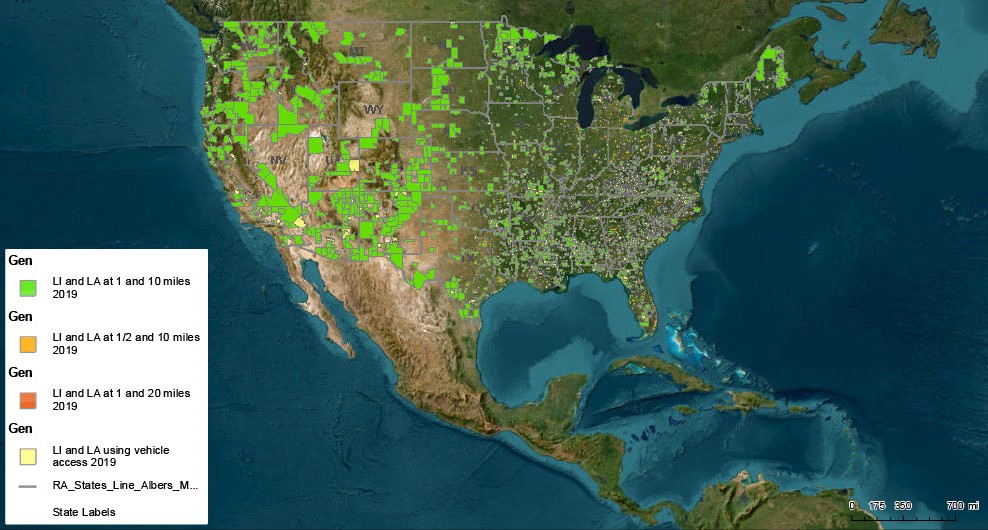

It is also home to few grocers, spare corner stores “probably with canned food,” Young says. For a number of residents, West Garfield Park may be a “food desert,” or an area with high concentrations of people but low concentrations of places for them to acquire fresh food. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Access Research Atlas, these food deserts surround the neighborhood, with pop-up grocers and similar community efforts seeking to fill the gap.

About 20% of households in the Chicago area experience food insecurity, which affects Black and Latino households nearly double the rate of white households, according to the Northwestern Institute for Policy Research . Nationwide, 5.6% to 17.4% of households are in low-income areas with low access to healthy food, according to the USDA .

Food, along with sleep and exercise, is considered one of the pillars of health. When one pillar falls, the others tumble down. So when people reside in a food desert, they also may live in a sleep desert, says Dr. Hrayr Attarian, a professor of neurology and sleep medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and medical director of Northwestern Medicine’s Sleep Health Center, central region.

The solution may not be as simple as having a greengrocer join a community. Experts point to the impact of structural racism, or systems and cultural factors that combine to foster racial inequality, on communities that may be food deserts.

“No, no one is stopping you from going to the grocery store,” says Dr. Attarian, who co-authored a recent paper about sleep deserts and the factors that create them. “But you get put in a place where you can’t easily go grocery shopping for healthy stuff. Even if there is healthy stuff, and it becomes more financially accessible, you may not have a place to live where you can have a good night’s sleep.”

‘It’s Not Just About Individual Behaviors’

What you eat matters, especially when it comes to sleep health.

Eating more fruits and vegetables can improve insomnia-related sleep difficulties , especially among women, according to one study. A 2023 SleepFoundation.org survey also found that adults who snack on healthy food may sleep at least a half-hour more each night than those who snack on “junk food.”

Sleeping more can make people eat less because it affects ghrelin, better known as the “hunger hormone.” Sleep-deprived adults may have elevated ghrelin levels, leading to more hunger and overeating, leading to obesity.

It’s all a part of the multidimensionality of sleep health, says Wendy M. Troxel, Ph.D., a senior behavioral scientist at the RAND Corp.

“The newer way of thinking about sleep is, it’s not just about individual behaviors driven by individual risk factors,” says Troxel, a SleepFoundation.org medical advisory board member. “But sleep is a behavior that’s deeply embedded in our social environments from our closest connections, the communities where we live, and the policies and structures under which we live. All of these can either foster or impinge upon our sleep.”

These connections became apparent to Dr. Attarian while teaching a class about health determinants and how they impact our bodies.

The class went to the West Side of Chicago, starting about 1.5 miles west from downtown and moving away from it. Dr. Attarian looked at buildings where his patients lived.

“They told me they were unable to sleep,” he says.

That’s when he realized his usual recommendation of having a quiet, dark, and cool place to sleep wasn’t feasible. It was bright, and it was loud. The recommendation of getting outside also didn’t fit: “There was no place to exercise because there’s no green space,” he says.

There go two of the pillars of health. And the impact touches just about all of the five senses.

“Sleep deserts usually happen in urban areas, where because of economic disadvantages, housing is crowded,” Dr. Attarian says. “The buildings are not as well-built as in wealthier areas. There often tends to be higher crime, and because of that, streetlights are on all the time.”

In addition to light pollution, thin walls mean more noise pollution in a building, which also may not have climate controls. So summer heat or winter temperatures create climate extremes that also impact a person’s ability to get a good night’s sleep, Dr. Attarian says.

Young says she experienced a similar situation in West Garfield Park, just west of the area Dr. Attarian walked. A nearby garbage incinerator ran until 1996, when it closed because of air-pollution concerns. But the sounds of the city kept going.

“You’ve got sirens, cars, motorcycles, you know, the city noise,” she says. “There’s always stuff going on in the neighborhood that interrupts your sleep in the middle of the night.”

How Did Things Get This Way?

In 2021, a Chicago Sun-Times analysis of city data found that shootings in West Garfield Park are nearly 20 times higher than in downtown Chicago. To put it in perspective: One study noted that young adult males had a greater probability of being killed there than U.S. soldiers did in Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s.

The Chicago Reader has called West Garfield Park “a community emblematic of the ravages of redlining.” Redlining refers to the practice shortly after the Great Depression of the federal government’s Home Owners Loan Corp. (HOLC) outlining areas of a map in red ink to indicate that their populations may have a higher perceived risk for a federally backed mortgage. Notes in a 1930s HOLC map reference Italian population in most of West Garfield Park, with high concentrations of Irish and Russian Jewish residents. Other notes, from the neighborhood’s north end: “This is a mediocre district threatened with negro encroachment.”

The Polis Center’s research says that redlining — plus zoning laws, racially restrictive housing covenants, and racial steering by real estate companies — forced many communities into specific, segregated geographic regions where adverse health outcomes increased, including diabetes and poorer self-reported health. The situation played out in cities from Los Angeles to Birmingham, Alabama, as well as in Chicago.

“It wasn’t just redlining, which was bad. It wasn’t just segregation. It was the capital extracted from neighborhoods that moved out, the loss of wealth,” says Dr. David Ansell, professor of internal medicine at Rush Medical College and senior vice president for community health equity at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

Dr. Ansell says that when businesses such as factories and retailers moved out, no similar employers had the desire or financial backing to replace them. That left residents without the means to generate wealth in their own communities.

The situation continues in neighborhoods such as West Garfield Park, now 87% Black. One of the last full-service grocery stores in West Garfield Park closed in 2021 “under the cover of night,” Dr. Ansell says. The parent company of the Aldi, which had been in the community for 30 years, cited “consistently declining sales” and said the store operated at a loss for years.

The Chicago Department of Health then temporarily closed the neighborhood’s last grocer, Save A Lot, after food inspectors found the grocery store infested with rats, leaving residents without a place to get fresh produce.

It has since re-opened, helped by Chicago’s City Council’s $13.5 million infusion via tax increment financing subsidies to Black-owned Yellow Banana, earmarked to rehabilitate six Save A Lot stores.

Meanwhile, in 2022, the city purchased the Aldi site with plans to attract another grocery store to the space.

Addressing Sleep at a Local Level

Throughout his career, Dr. Ansell says the degree of disease he’s seen in his patients “somehow seemed correlated, at least physiologically, with the state of the neighborhood itself.”

“It’s something I’d never learned in medical school,” Dr. Ansell says.

Life expectancy in West Garfield Park is anywhere from 66 to 71 years old , depending on the source. That’s still at least a dozen years less than downtown Chicago a few miles to the east. Life expectancy can vary by as much as 30 years in other parts of the city.

As for sleep: According to a meta-analysis of SleepFoundation.org surveys in 2022 and 2023, residents of seven U.S. ZIP codes that fall within the definition of a food desert average 6 hours, 42 minutes of sleep each night. That’s considered short sleep.

“There’s now growing recognition that the disparities we see in sleep, based on race, ethnicity as well as socioeconomics, are rooted in structural causes, including structural racism,” Troxel says. “Where people live is not by accident. There are policy-level factors that have contributed to the fact that Blacks, Hispanics, and American Indian, Alaskan natives are more likely to live in lower-income areas and more segregated areas.”

That’s why David Bishop, 54, a licensed clinical social worker with obstructive sleep apnea, created the Sleep Equity Project, a nonprofit focused on addressing sleep disparities in the Chicago area. After seeing a study stating more men than women died of sleep apnea , especially Black men who lived in the Midwest, Bishop became alarmed.

“I’m African-American, and for sleep apnea, the mortality rate for Black men is rising ,” says Bishop, who was born and raised in the Washington Heights neighborhood on Chicago’s far South Side but now lives in Oak Park. “I have some urgency to figure out how to address these issues.”

Launched in November 2022, the nonprofit collaborates with local and national sleep physicians and researchers to help Chicagoans become more informed about sleep disorders, Bishop says. That may be easier said than done, he says: Primary-care physicians may not be experts on sleep. The most impactful sleep apnea conversations may happen somewhere like a barber shop, Bishop says.

Young, a Sleep Equity Project board member, was diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea while she lived in West Garfield Park. She says her sleep study uncovered that she stopped breathing 72 times an hour; by definition, “severe” obstructive sleep apnea is anything higher than 30 episodes of 10-second reduced-breathing periods per hour.

Bishop also aims to help more people of color find financial resources that may support paying for sleep medicine with prescription resources, connections to professional organizations, and sharing how to write a letter of medical necessity to seek assistance.

Dr. Attarian says socioeconomic barriers make it extremely difficult for many Chicagoans in underserved communities to achieve adequate sleep, exercise, and proper nutrition — the trifecta for creating good health.

It’s cyclical, as Bishop explains: “When you have insufficient sleep, that can trigger the craving for carbs and sugars . And if you have a community that doesn’t have availability of nutritious food, that can contribute to obesity and poor health. It’s interconnected.

“When you have a poor sleep environment and food deserts, that’s a one-two punch for even poorer health.”

Searching For Solutions

Addressing the social and structural underpinnings of poor health is key to tackling the issues we can see with our eyes, from a lack of grocers to sleep-deprived residents, Dr. Ansell says.

So in West Garfield Park, a group of residents, health-care institutions, including Rush University Medical Center, and nonprofits formed the Garfield Park Rite to Wellness Collaborative to improve health outcomes and life expectancy rates.

The collaborative is working on a $50 million project, a health-and-wellness community called Sankofa Wellness Village, recipient of a $10 million grant from the Pritzker Traubert Foundation.

Plans for the wellness village include a health center, a credit union, a café, early childhood education, community programming, an arts center, and an entrepreneurial development center — as well as a community grocer.

It’s just one of the efforts in Chicago and nationwide to address how we live and how we sleep. And they begin, Dr. Ansell says, with hearing what people in these areas have to say.

“The community … said we want jobs, good paying jobs,” he says. “We want support for local businesses. We want safe places to work and walk. We want mental health. We want access to healthy food, and we don’t want to have to drive to Oak Park to get food.”

References

12 Sources

-

Schanzenbach, Diane, Pitts, Abigail. (2020 May 13). Estimates of Food Insecurity During the COVID-19 Crisis: Results from the COVID Impact Survey, Week 1. Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University.

https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/documents/reports/food-insecurity-covid_week1_report-13-may-2020.pdf -

USDA ERS – Documentation. (n.d.)., Retrieved April 6, 2023, from

https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/documentation/ -

Attarian, H., Mallampalli, M., & Johnson, D. (2022). Sleep deserts: a key determinant of sleep inequities. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 18(8), 2079–2080.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35499144/ -

Jansen, E. C., She, R., Rukstalis, M., & Alexander, G. L. (2021). Changes in fruit and vegetable consumption in relation to changes in sleep characteristics over a 3-month period among young adults. Sleep health, 7(3), 345–352.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33840631/ -

Robinson, M, Andromalos, L, Brigham Health Hub. Sleep More to Eat Less: How Sleep Affects the “Hunger Hormone”., Retrieved March 8, 2023.

https://brighamhealthhub.org/controlling-the-hunger-hormone/ -

Broussard, J. L., Kilkus, J. M., Delebecque, F., Abraham, V., Day, A., Whitmore, H. R., & Tasali, E. (2016). Elevated ghrelin predicts food intake during experimental sleep restriction. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 24(1), 132–138.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26467988/ -

Del Pozo, B., Knorre, A., Mello, M. J., & Chalfin, A. (2022). Comparing Risks of Firearm-Related Death and Injury Among Young Adult Males in Selected US Cities With Wartime Service in Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA network open, 5(12), e2248132..

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36547982/ -

Townsley, Jeramy, Andres, Unai Miguel, Nowlin, Matt. (2021 June 1) The Lasting Impacts of Segregation and Redlining. The Polis Center, IU Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering at IUPUI., Retrieved March 9, 2023, from

https://www.savi.org/2021/06/24/lasting-impacts-of-segregation/ -

DPD Obtains Authority to Acquire West Garfield Park Aldi Site. (2022, February 23). City of Chicago., Retrieved April 6, 2023, from

https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/dcd/provdrs/ec_dev/news/2022/february/dpd-obtains-authority-to-acquire-west-garfield-park-aldi-site.html -

Life Expectancy: Could where you live influence how long you live? (n.d.). Robert Wood Johnson Foundation., Retrieved April 6, 2023, from

https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/interactives/whereyouliveaffectshowlongyoulive.html -

Lee, Y. C., Chang, K. Y., & Mador, M. J. (2022). Racial disparity in sleep apnea-related mortality in the United States. Sleep medicine, 90, 204–213.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35202926/ -

St-Onge, M. P., Wolfe, S., Sy, M., Shechter, A., & Hirsch, J. (2014). Sleep restriction increases the neuronal response to unhealthy food in normal-weight individuals. International journal of obesity (2005), 38(3), 411–416.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23779051/