How to Become a Morning Person

Whether it is break-of-dawn school start times or early work meetings, most schedules seem to accommodate morning people.

If you are wondering how to become a morning person, there are several factors to consider. Being a night owl is hardwired to some extent, due to a phenomenon called chronotypes. That said, there are tactics you can use to make yourself feel more comfortable in the morning.

We will explain the science behind chronotypes, and share tips for becoming more of a morning person.

Tips for Becoming a Morning Person

People change their sleep schedules for all sorts of reasons. If you need to become more of a morning person to support a new work or school schedule, help out your family, or simply because you want to, it may help to follow these tips.

Maintain Good Sleep Hygiene

Before you start shifting your sleep schedule, it is beneficial to establish healthy sleep practices, commonly referred to as sleep hygiene. Sleep hygiene encompasses a set of habits that are said to promote better sleep, such as:

- Exercising regularly

- Avoiding caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol, especially before bed

- Avoiding afternoon and evening naps

- Finding relaxing pre-bed activities

Sleep hygiene also involves making your bedroom conducive to better sleep by creating a dark, quiet, and cool bedroom environment. It may help to use blackout curtains, invest in high-quality bedding, and clear the room of clutter.

Develop a Nighttime Routine

A bedtime routine signals to your brain that it is time to fall asleep. This type of behavioral cue is all the more powerful when you perform the same activities in the same order, night after night, before going to bed.

Dim the lights and avoid using any electronics during your bedtime routine, such as your smartphone, TV, or an e-reader. Instead, fill your bedtime routine with calming, restful activities that can help your body wind down for sleep. Consider taking a bath, reading a book, journaling, listening to relaxing music, or doing some light stretching or meditation.

Stay on a Consistent Sleep Schedule

Whether you are an evening person or a morning person, having a consistent sleep schedule makes it easier to get at least seven hours of sleep per night and feel more refreshed during the day. Studies have found that sleeping in on the weekends can disrupt your circadian rhythm, so it is best to set regular sleep and wake times and follow them daily.

Gradually Shift Your Bedtime Earlier

Once you have adopted a regular sleep schedule, start shifting your bedtime earlier, using increments of 15 minutes. At the same time, adjust your alarms to wake up 15 minutes earlier. Make the change gradually, taking at least a few days in between each new shift.

Develop a Morning Routine

Filling your morning routine with things that make you feel happy and energized may help you feel more motivated to get out of bed. That could include your favorite morning beverage, or sitting outside with your beloved pet for a few minutes.

If you use an alarm, research shows that more melodic alarm noises make it easier to shake off the groggy feeling known as sleep inertia. You could also consider letting light serve as a natural alarm clock, either by leaving the curtains open or by using a dawn simulator that coaxes you gently from sleep. Ideally, people who receive adequate sleep may not even need an alarm clock.

Exercise Regularly

Keeping a regular exercise routine is proven to help improve sleep. One group of researchers found that morning and evening exercise alike have a particularly profound effect on the circadian rhythms of night owls , and may help them bring their sleep cycles approximately 30 minutes earlier.

Use Light Strategically

Light has a strong alerting effect that exerts a powerful influence on the circadian rhythm. Some research indicates that it may have a stronger effect on night owls. When night owls are exposed only to natural light, their internal body clocks shift earlier. Exposure to bright light in the morning is considered one of the best ways to become more of a morning person and shift your chronotype earlier. If you cannot go outside, sit by a window or buy a light therapy lamp that is designed to imitate natural light.

Shift Mealtimes Earlier

Your appetite is intricately tied to your circadian rhythm, and the timing of your meals can have an effect on your circadian rhythm. While it is common for night owls to eat meals later, eating at a time closer to a morning person’s schedule can help your body adjust to an earlier routine.

Be Careful With Coffee

Studies show that drinking caffeine up to six hours before bedtime can disrupt your sleep and make it harder to drift off. Try to avoid consuming more than 400 milligrams of caffeine daily and schedule your last cup of coffee for at least six hours before bed, if not earlier.

Why Are Some People Morning People and Not Others?

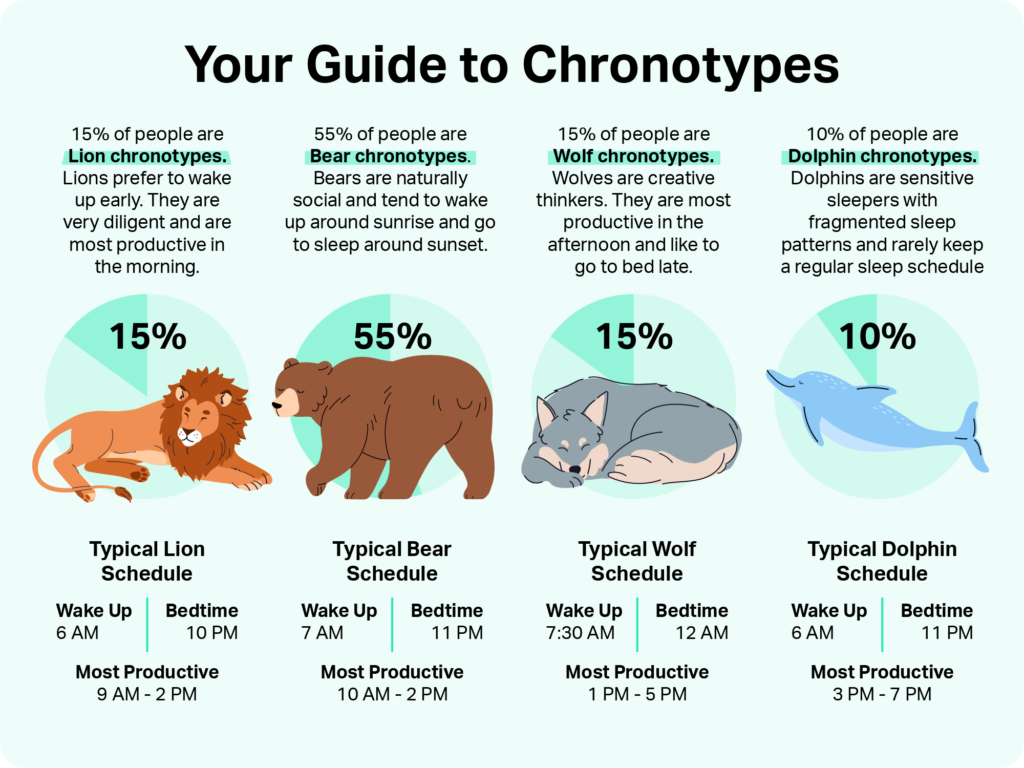

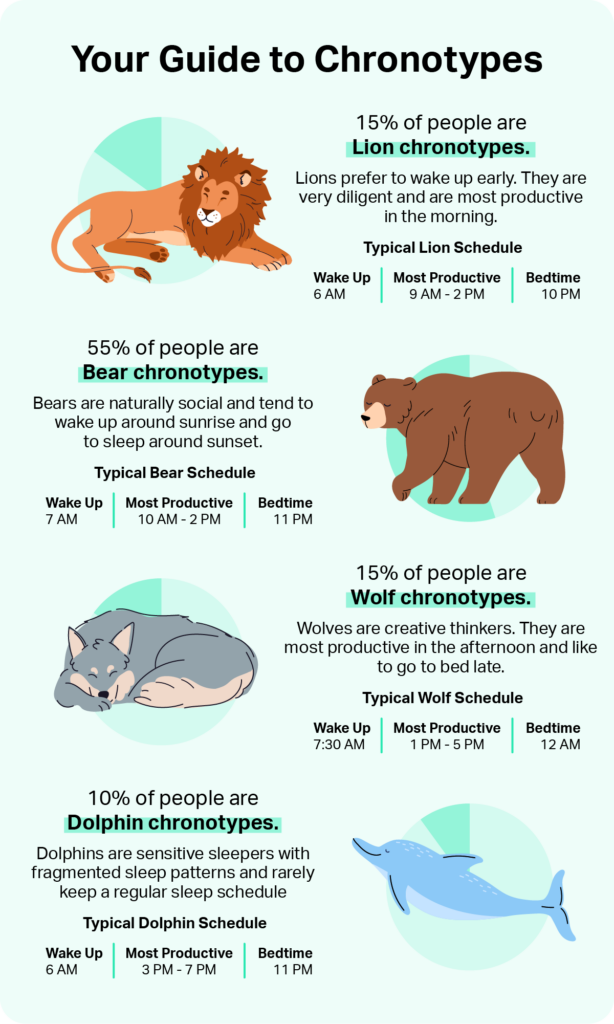

Our sleep-wake cycles are dictated by our circadian rhythm, an internal body clock that regulates our energy levels throughout the day. The circadian rhythm operates on a 24-hour schedule that generally follows the patterns of the sun. Most people feel awake when it is light and sleepy when it is dark, but the specific timing of these schedules can vary from person to person. That variability is what is known as a chronotype.

Morning people, or early birds, have an early chronotype. They like waking up early and they tend to feel at their best earlier in the day. Night owls, on the other hand, have a late chronotype. They prefer to wake up later and they feel most motivated and active at night. Chronotypes lie on a spectrum, and most people fall somewhere in between.

Chronotypes are reflected at a physiological level, all the way down to the central nervous system . In morning people, brain pathways are most excitable in the morning, empowering peak performance early in the day. In night owls, it is the opposite.

Neither chronotype is inherently better than the other, however night owls are at a disadvantage in many ways. From school to work, important activities are often scheduled for the morning, when night owls are still sleepy and experience lower cognitive and physical performance as a result.

Can You Change Your Chronotype?

Your chronotype is largely genetic, but your age, environment, and activity level can all influence it. For example, in one study, night owls were able to shift their sleep cycle forward by as much as two hours through a handful of ordinary lifestyle changes. Night owls in the study were able to shift their sleep cycles forward, without negatively impacting the total amount of sleep they got each night. Moreover, they declared feeling less depressed and less stressed. When researchers carried out tests of their reaction times and grip strength, they found the night owls performed better than before in the morning, which was usually their weakest time of day.

Your chronotype may also shift due to age, gender, and physical changes. For example, one study found that women are more likely than men to be early birds from childhood through their 20s, but are more likely than men to become night owls after age 45. The chronotypes of pregnant people shift earlier during the first and second trimesters, before returning to normal during the third trimester. Having a stroke may also affect your chronotype.

Still have questions? Ask our community!

Join our Sleep Care Community — a trusted hub of sleep health professionals, product specialists, and people just like you. Whether you need expert sleep advice for your insomnia or you’re searching for the perfect mattress, we’ve got you covered. Get personalized guidance from the experts who know sleep best.

References

10 Sources

-

Consensus Conference Panel, Watson, N. F., Badr, M. S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D. L., Buxton, O. M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D. F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M. A., Kushida, C., Malhotra, R. K., Martin, J. L., Patel, S. R., Quan, S. F., Tasali, E., Non-Participating Observers, Twery, M., Croft, J. B., Maher, E., … Heald, J. L. (2015). Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(6), 591–592.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25979105/ -

Crowley, S. J., & Carskadon, M. A. (2010). Modifications to weekend recovery sleep delay circadian phase in older adolescents. Chronobiology International, 27(7), 1469–1492.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20795887/ -

McFarlane, S. J., Garcia, J. E., Verhagen, D. S., & Dyer, A. G. (2020). Alarm tones, music and their elements: Analysis of reported waking sounds to counteract sleep inertia. PLOS ONE, 15(1), e0215788.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31990906/ -

Thomas, J. M., Kern, P. A., Bush, H. M., McQuerry, K. J., Black, W. S., Clasey, J. L., & Pendergast, J. S. (2020). Circadian rhythm phase shifts caused by timed exercise vary with chronotype. JCI Insight, 5(3), e134270.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31895695/ -

Wehrens, S., Christou, S., Isherwood, C., Middleton, B., Gibbs, M. A., Archer, S. N., Skene, D. J., & Johnston, J. D. (2017). Meal timing regulates the human circadian system. Current Biology, 27(12), 1768–1775.e3.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28578930/ -

Drake, C., Roehrs, T., Shambroom, J., & Roth, T. (2013). Caffeine effects on sleep taken 0, 3, or 6 hours before going to bed. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 9(11), 1195–1200.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24235903/ -

Tamm, A. S., Lagerquist, O., Ley, A. L., & Collins, D. F. (2009). Chronotype influences diurnal variations in the excitability of the human motor cortex and the ability to generate torque during a maximum voluntary contraction. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 24(3), 211–224.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19465698/ -

Duarte, L. L., Menna-Barreto, L., Miguel, M. A., Louzada, F., Araújo, J., Alam, M., Areas, R., & Pedrazzoli, M. (2014). Chronotype ontogeny related to gender. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 47(4), 316–320.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24714814/ -

Martin-Fairey, C. A., Zhao, P., Wan, L., Roenneberg, T., Fay, J., Ma, X., McCarthy, R., Jungheim, E. S., England, S. K., & Herzog, E. D. (2019). Pregnancy induces an earlier chronotype in both mice and women. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 34(3), 323–331.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31018734/ -

Kantermann, T., Meisel, A., Fitzthum, K., Penzel, T., Fietze, I., & Ulm, L. (2015). Changes in chronotype after stroke: A pilot study. Frontiers in Neurology, 5, 287.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25628597/