When you buy through our links, we may earn a commission. Products or services may be offered by an affiliated entity. Learn more.

ASV Machines

- Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) machines may be used to treat complex sleep apnea and central sleep apnea.

- These devices monitor breathing patterns and adjust airway pressure as needed.

- ASV machines are relatively new and there is little research on their potential effects.

- Ask a sleep specialist about ASV therapy as a potential treatment option if you experience central or mixed sleep apnea.

Sleep apnea is a common sleep disorder in the U.S., affecting 10% to 30% of adults. Sleep apnea is commonly treated using positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy , which can be in the form of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP), or a newer form called adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV).

PAP machines deliver air pressure to keep a person’s airways open while they sleep, via a mask they wear over their nose (or nose and mouth). When used as prescribed, PAP therapy can help stabilize breathing during sleep, reduce daytime sleepiness, and improve overall quality of life for many people with sleep apnea.

The most basic PAP device is the CPAP device, which delivers a steady stream of air as the person inhales and exhales. A BiPAP device can be set to two different strengths for inhaling or exhaling. These devices tend to work well for treating obstructive sleep apnea. ASV therapy is more commonly used for people who also experience central sleep apnea.

Is Your Snoring a Health Risk?

Answer three questions to understand if you should be concerned.

What Are ASV Machines?

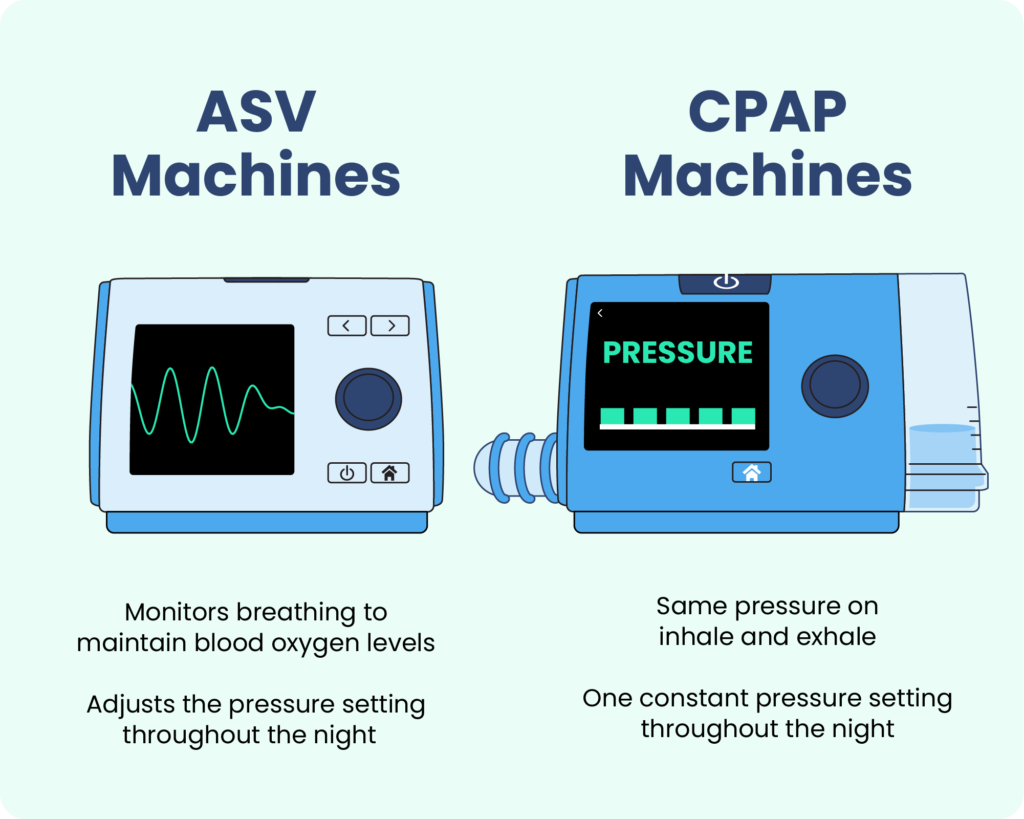

Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) machines monitor a person’s breathing while they sleep and deliver customized air pressure to stabilize breathing . The main difference between ASV and CPAP machines is that ASV machines deliver air pressure dynamically, adjusting according to the person’s breathing patterns, whereas CPAP machines deliver a set level of air pressure throughout the night. Each device has specific benefits depending on the type of sleep apnea.

Both central and obstructive sleep apnea cause temporary pauses in breathing, called apneic events. Obstructive sleep apnea causes apneic events when the airway narrows or becomes blocked. In central sleep apnea, apneic events occur when the brain fails to signal the respiratory muscles to breathe, as opposed to a physical relaxation or obstruction of the muscles. Some people with obstructive sleep apnea may develop central sleep apnea when using CPAP therapy, which is known as complex sleep apnea, or treatment-emergent central sleep apnea .

Researchers have proposed several reasons why CPAP therapy might contribute to central apneic events. For people with over-sensitive breathing mechanisms, the reduced levels of carbon dioxide in the blood or the expanded lungs due to the CPAP device may send a signal to the brain that there is no need to breathe. For people with congestive heart failure, this problem might be compounded if the heart is also responding to changes induced by the CPAP therapy.

Sometimes, these problems resolve on their own as the person becomes accustomed to the CPAP device. However, for people who continue to experience central apneic events, ASV can encourage a more regular breathing pattern. By lowering the air pressure when the person is breathing normally, the ASV machine helps avoid situations in which the brain decides to stop breathing based on the low levels of carbon dioxide in the blood. Since ASV also delivers air mechanically, it also helps treat obstructive sleep apnea events .

How Do ASV Machines Work?

Like CPAP devices, ASV machines consist of three basic parts: a face mask, the machine, and a flexible hose that connects the mask to the machine. Before falling asleep, the person puts on the mask and turns on the machine. ASV masks may either be fitted over the nose and the mouth, or just the nose .

The ASV device monitors a person’s breathing throughout the night. If a person’s breathing slows down, the machine responds with enough pressure to return them to normal breathing levels. Once their breathing goes back to normal, the ASV machine lowers the pressure, but may still provide a baseline level of support to make it easier for the person to breathe normally.

This method helps regularize breathing for people who respond poorly to CPAP therapy , and the variability in air pressure may also relieve some of the discomfort people feel with CPAP therapy .

ASV vs. CPAP: What’s the Difference?

As opposed to ASV machines, both CPAP and regular BiPAP devices deliver air pressure in a pre-set way:

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines deliver a set amount of air pressure continuously throughout the night.

- Bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) machines can be adjusted to provide a different level of pressure when the person exhales.

Unlike CPAP and BiPAP machines, ASV devices adapt to the individual throughout the night, using algorithms to adjust the air pressure as necessary to fit their breathing patterns.

Both ASV and BiPAP machines can also provide a backup respiratory rate, which helps maintain breathing during central apneic events. ASV machines differ in that this backup respiratory rate can be personalized based on ongoing feedback from the person’s breathing patterns.

Risks and Side Effects of ASV

While ASV therapy is effective, it is not recommended for everyone. Specifically, there are higher risks for people with a certain type of congestive heart failure that affects pumping, called reduced ejection fraction. For this reason, experts do not recommend using ASV to treat central sleep apnea in people with this type of heart failure.

Similar to CPAP machines, ASV machines can cause some side effects and discomfort, such as:

- Aerophagia (air swallowing)

- Congestion

- Difficulty sleeping due to mask discomfort

- Dry mouth

- Eye irritation

- Mask leak

- Mouth leak

- Nostril irritation

- Skin irritation or creasing from the mask

Using a humidifier may decrease symptoms such as dry mouth.

Compared to CPAP therapy, ASV machines are generally less likely to cause feelings of claustrophobia when exhaling against pressurized air. This feeling is a common reason why people stop using CPAP therapy.

There is relatively little research on the potential risks and side effects of ASV machines . Companies may also use proprietary algorithms to determine airflow rates, making it difficult to compare across models.

Who Is ASV Best For?

ASV was originally developed for people with Cheyne-Stokes respirations, a condition linked to heart failure that involves hyperventilation followed by lapses in breathing . ASV therapy is also used to treat sleep-disordered breathing in people with:

- Central sleep apnea (CSA), including CSA due to stroke, kidney failure, neurological conditions, or opioid use

- Complex sleep apnea, or treatment-emergent central sleep apnea, which arises during OSA treatment

- Mixed sleep apnea, involving obstructive and central apneic events

BiPAP and ASV therapy have proven to be more effective than CPAP therapy in cases of drug-induced sleep-disordered breathing, which can affect people taking opioids for pain management or with former drug abuse. There is also interest in using ASV therapy to improve breathing for people with central sleep apnea due to neurological disorders. Additionally, ASV therapy can be effective for people who do not respond to CPAP treatment, such as people who have both chronic complex insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea.

Typically, CPAP is attempted before ASV. ASV therapy is more expensive, and CPAP therapy is often successful at treating obstructive sleep apnea as long as people continue to use the device . That said, many people find ASV machines to be more comfortable, which may make it easier to adhere to their treatment.

Whatever type of device you are using to manage your sleep apnea, it is best to consult with your doctor about any discomfort you are feeling. They can adjust your machine settings, or recommend a different type of device to help you breathe and sleep easier through the night.

Still have questions? Ask our community!

Join our Sleep Care Community — a trusted hub of sleep health professionals, product specialists, and people just like you. Whether you need expert sleep advice for your insomnia or you’re searching for the perfect mattress, we’ve got you covered. Get personalized guidance from the experts who know sleep best.

References

16 Sources

-

Kline, L. R. (2022, April 1). Clinical presentation and diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. In N. Collop (Ed.). UpToDate., Retrieved September 15, 2022, from

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-and-diagnosis-of-obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults -

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (n.d.). Sleep apnea., Retrieved August 30, 2021, from

https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/sleep-apnea -

Aurora, R. N., Bista, S. R., Casey, K. R., Chowdhuri, S., Kristo, D. A., Mallea, J. M., Ramar, K., Rowley, J. A., Zak, R. S., & Heald, J. L. (2016). Updated adaptive servo-ventilation recommendations for the 2012 AASM Guideline: “The treatment of central sleep apnea syndromes in adults: Practice parameters with an evidence-based literature review and meta-analyses.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 12(5), 757–761., Updated adaptive servo-ventilation recommendations for the 2012 AASM Guideline: “The treatment of central sleep apnea syndromes in adults: Practice parameters with an evidence-based literature review and meta-analyses.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 12(5), 757–761.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27092695/ -

Batool-Anwar, S., Goodwin, J. L., Kushida, C. A., Walsh, J. A., Simon, R. D., Nichols, D. A., & Quan, S. F. (2016). Impact of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) on quality of life in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Journal of Sleep Research, 25(6), 731–738.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27242272/ -

Park, P., Kim, J., Song, Y. J., Lim, J. H., Cho, S. W., Won, T. B., Han, D. H., Kim, D. Y., Rhee, C. S., & Kim, H. J. (2017). Influencing factors on CPAP adherence and anatomic characteristics of upper airway in OSA subjects. Medicine, 96(51), e8818.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29390419/ -

Jaffuel, D., Philippe, C., Rabec, C., Mallet, J. P., Georges, M., Redolfi, S., Palot, A., Suehs, C. M., Nogue, E., Molinari, N., & Bourdin, A. (2019). What is the remaining status of adaptive servo-ventilation? The results of a real-life multicenter study (OTRLASV-study): Adaptive servo-ventilation in real-life conditions. Respiratory Research, 20(1), 235.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31665026/ -

Sharma, B. K., Bakker, J. P., McSharry, D. G., Desai, A. S., Javaheri, S., & Malhotra, A. (2012). Adaptive servoventilation for treatment of sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest, 142(5), 1211–1221.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22722232/ -

Zhang, J., Wang, L., Guo, H. J., Wang, Y., Cao, J., & Chen, B. Y. (2020). Treatment-emergent central sleep apnea: A unique sleep-disordered breathing. Chinese Medical Journal, 133(22), 2721–2730.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33009018/ -

Cowie, M. R., Woehrle, H., Oldenburg, O., Damy, T., van der Meer, P., Erdman, E., Metra, M., Zannad, F., Trochu, J. N., Gullestad, L., Fu, M., Böhm, M., Auricchio, A., & Levy, P. (2015). Sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure – current state of the art. Cardiac Failure Review, 1(1), 16–24.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28785426/ -

Cantero, C., Adler, D., Pasquina, P., Uldry, C., Egger, B., Prella, M., Younossian, A. B., Poncet, A., Soccal-Gasche, P., Pepin, J. L., & Janssens, J. P. (2020). Adaptive servo-ventilation: A comprehensive descriptive study in the Geneva Lake area. Frontiers in Medicine, 7, 105.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32309284/ -

Pépin, J. L., Woehrle, H., Liu, D., Shao, S., Armitstead, J. P., Cistulli, P. A., Benjafield, A. V., & Malhotra, A. (2018). Adherence to positive airway therapy after switching from CPAP to ASV: A big data analysis. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 14(1), 57–63.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29198291/ -

Krakow, B., McIver, N. D., Ulibarri, V. A., Krakow, J., & Schrader, R. M. (2019). Prospective randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of continuous positive airway pressure and adaptive servo-ventilation in the treatment of chronic complex insomnia. EClinicalMedicine, 13, 57–73.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31517263/ -

Pinto, V. L., & Sharma, S. (2021). Continuous positive airway pressure. StatPearls.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29489216/ -

Selim, B., & Ramar, K. (2016). Advanced positive airway pressure modes: Adaptive servo ventilation and volume assured pressure support. Expert Review of Medical Devices, 13(9), 839–851.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27478974/ -

Rudrappa, M., Modi, P., & Bollu, P. C. (2021). Cheyne Stokes respirations. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28846350/ -

Mehrtash, M., Bakker, J. P., & Ayas, N. (2019). Predictors of continuous positive airway pressure adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Lung, 197(2), 115–121.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30617618/